( for ![]() or

or

![]() )

)

Washington Post

IBM Technology Aided Holocaust, Author Alleges

By Michael Dobbs, Washington Post Staff Writer

Sunday, February 11, 2001; Page A22

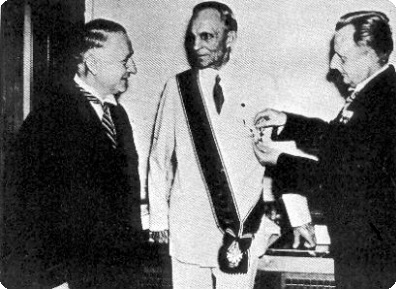

"In June 1937, Thomas J. Watson, founder of 'International Business Machines Corp.',  accepted an honor that would come to haunt him, a

medal created by Adolf Hitler for foreign citizens "who made themselves

deserving of the German Reich." Embedded with swastikas and

eagles, the medal was dramatic confirmation of IBM's contribution to the

automation of Nazi Germany.

accepted an honor that would come to haunt him, a

medal created by Adolf Hitler for foreign citizens "who made themselves

deserving of the German Reich." Embedded with swastikas and

eagles, the medal was dramatic confirmation of IBM's contribution to the

automation of Nazi Germany.

At the time, Germany was second only to the United States as IBM's best

customer. Historians have since documented how IBM punch-card technology, the precursor to the computer, did everything from helping to make

German trains run on time to facilitating Hitler's rearmament program to

tabulating the census data that were an important element in the Nazi

leader's murderous racial politics.

A new book takes the case against Watson and IBM a big step further, and

argues that custom-built IBM technology helped fuel the Holocaust by

permitting Hitler to automate his persecution of the Jews and by generating

lists of groups slated for deportation to Nazi death camps. It relates how,

after IBM lost control over its German operation in 1941 and Watson returned

his medal, its technology was used in Auschwitz and other Nazi death camps

to register inmates and track slave labor.

"IBM technology put the blitz into the blitzkrieg and the fantastical numbers

into the Holocaust," argued Edwin Black, a former journalist and son of

Holocaust survivors who spent three years studying IBM's involvement in

Nazi Germany for his book, "IBM and the Holocaust." "The Holocaust would

have occurred with or without IBM - but the Holocaust that we know of, the

Holocaust of the fantastic numbers, this is the Holocaust of IBM technology.

It enabled the Nazis to achieve scale, velocity, efficiency."

Black's conclusions have stirred debate among Holocaust scholars and

experts even before his 500-page book becomes widely available Monday.

Some historians have endorsed Black's findings that IBM and its German

subsidiary played a critical role in Nazi persecution. Others insist that IBM

technology had little to do with the Holocaust, and that the Nazis used pre-

dominantly conventional methods to keep track of Jews.

"The notion that the Nazis needed sophisticated technology to be efficient is

wrong," said Raul Hilberg, author of "The Destruction of the European Jews"

and widely regarded as a leading scholar on the Jewish deportation process.

"Efficiency can be produced by people, with what we regard as very primitive

means, like pencil and paper. You have to be very careful. The

Nazis had machines, they were efficient. That is fine, but this is not a

cause-and-effect proposition."

An IBM spokeswoman, Carol Makovich, said it was difficult for IBM to comment

on Black's book as the company was not permitted to see it before publication.

She said IBM was eager to cooperate with independent researchers and had

deposited relevant archives with New York University and Hohenheim University in Stuttgart, Germany. But she said that records regarding the

company's activities in Nazi Germany were "incomplete and inconclusive."

"Of course, IBM deplores the Nazi regime and its atrocities," she said.

The publication of "IBM and the Holocaust" has been shrouded in secrecy on

the grounds of protecting "journalistic exclusivity." Instead of circulating

the book among reviewers, Crown Publishers arranged for excerpts to appear

in Newsweek magazine and foreign publications and for Black to appear on

talk shows. An advance copy of "IBM and the Holocaust" was made

available to The Washington Post under embargo until today. Publishers

sometimes use such a strategy to heighten commercial demand for a provocative book while shielding it from unfavorable reviews or rebuttal."

The most controversial allegation in Black's book is that IBM punch-card

technology was used to generate lists of Jews and other victims who were

then targeted for deportation. While there is no question that IBM New

York permitted its technology to be used in Nazi census operations, including

the German censuses of 1933 and 1939, there is debate over how useful the

census data were in locating individuals.

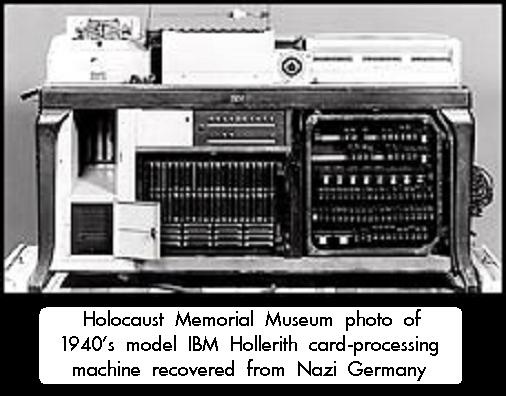

"Punch-card technology, which gained dubious fame in the November U.S.

presidential election, can be traced to 1884. Herman Hollerith, a

20-year-old German American engineer, invented a device for storing data

on cards through a series of holes, each representing a different piece of

information, such as age, education, location and religion. The cards

were sorted by machine to produce cross-tabulated data.

In the pre-computer era, Hollerith machines were the most sophisticated

information technology available. They were put to thousands of

uses, from cracking enemy codes to tracking military equipment to compiling

census data. From the mid-1920s, punch cards were the principal vehicle for

IBM's worldwide expansion. IBM patented the technology and guarded

it from competitors, leasing machines to customers and keeping tight control

over the supply of punch cards.

Hollerith technology offered the Nazis a powerful tool of social control, as

IBM officials quickly recognized. A few weeks after Hitler came to

power in 1933, the head of IBM's German subsidiary, "German Hollerith Machines"

(abbreviated as DAHOMAG ) dedicated his company's services to the Third Reich :

"We are recording the individual characteristics of every single member of the nation on a little (IBM) card.

We are proud to be able to contribute to such a task, a task that provides the physician of our German body politic [Hitler] with the material for his examination, so that our physician can determine whether, from the standpoint of the nation's health, the computed data correlates in a harmonious, that is, healthy, relationship�"or whether diseased conditions must be cured by corrective interventions.... We have firm confidence in our physician and will follow his orders in blind faith, for we know that he will lead our nation toward a great future.

Heil to our German people and their leader!"

By the outbreak of World War II in 1939, IBM was supplying Nazi Germany

with more than a billion punch cards a year, according to Black's research.

The German government "needs our machines," a senior IBM official reported

in March 1941, nine months before the United States declared war on Hitler.

"The army is using them presently for every conceivable purpose."

The once-warm relations between IBM and Nazi Germany deteriorated

sharply after June 1940, when Watson returned his Eagle with Star medal

to Hitler with the explanation that he could no longer support "the policies

of your government." Over the next year, records show, Watson lost control

of IBM's German subsidiary to Heidinger, a Nazi party member who had

long feuded with IBM New York over profits and operations.

IBM spokeswoman Makovich said it was unclear precisely when IBM New

York lost control over its German subsidiary, Dehomag. She said the

Nazis became increasingly involved in Dehomag's operations starting in

1933, even though IBM still had an 84 percent stake in the company when

the United States declared war on Germany in December 1941. She

added that Watson was awarded the Nazi medal as president of the International Chamber of Congress for "promoting world peace through world

trade" rather than as head of IBM.

After 1941, Dehomag became brazen about the licensing of Hollerith technology for the persecution of Nazi victims. Records show that the

Hollerith machines were used in at least a dozen concentration camps,

including Auschwitz, Buchenwald and Dachau. Prisoners were

assigned individual Hollerith numbers and given a designation based on

16 categories, such as 3 for homosexual, 8 for Jew and 13 for prisoner of

war.

While there is no evidence that IBM New York knew Hollerith machines

were being used in places such as Auschwitz, Black maintains that the

company profited from Dehomag's activities and was fully reimbursed

after the war.

"IBM was paid for the cards," Black said. "They did not say that

these cards were issued without their permission. The last Reich Mark paid to IBM was a check handed to a U.S. military officer."

William Seltzer, an expert in demographic statistics at Fordham University

in New York City and a former consultant to the U.N. war crimes tribunal,

said: "To me there is no doubt that [IBM] technology was used for evil ends.

To me that is not the issue. The issue is whether Watson knew; I

am not saying that Watson was a Nazi. He was out for his company

and out for his technology, and pretty blind to the way it was being used."

Historians differ on whether the information collected through punch-card

technology gave the Nazis an ability they otherwise would not have had

to persecute Jews and other minorities. Black argues that the census

data permitted the Nazis to establish detailed deportation quotas for individual localities and divide the Jewish population into full Jews, half Jews,

quarter Jews, and so on. These classifications frequently determined

the fate of individuals.

But Hilberg pointed out that the Nazis had numerous sources of information about the Jewish population, including police registrations and records

collected from Jewish communities by the Gestapo.

The strongest case for the use of Hollerith technology in detaining Jews is

probably Holland following the 1940 Nazi takeover. Black unearthed

records showing that Dutch population experts acting under Nazi instructions

used the punch-card system to tabulate lists of Jews who were later slated

for deportation. Black pointed out that the death rate among Dutch

Jews during the Nazi period was 73 percent, compared to around 25 percent

in France, where the punch-card system was less common.

Other experts caution that it is too simplistic to attribute the differing

death rates to the use of punch-card technology.

"There were other factors involved," said Bob Moore, a Holocaust historian

at the University of Sheffield in England. "There was no general population registration in France, as there was in the Netherlands. Furthermore, the Dutch are traditionally much more respectful of authority than the

French. If someone sends you a form in Holland, you fill it in properly. In France, it is the opposite."

Some historians are troubled by the lack of scholarly review of Black's work,

and note that a 1984 book he wrote on relations between Nazi Germany and

Zionist officials in Palestine, "The Transfer Agreement," generated similar

controversy. While Black's manuscript was circulated to some experts,

including Moore and Seltzer, it has not been reviewed by other leading

Holocaust historians."

James Mooney, General Motors' chief executive for overseas operations, 1938

and the worst of them all, the founder of Ford Motor Co., Henry Ford, in 1938

Hollywood's Creepy Love Affair With Adolf Hitler,

|

Contact [email protected] There is much more where this came from, at and/or |